Among the vast number of things children need to learn about language is how to appropriately refer to other people. One way to do this is to use kinship terms—words like ‘great-grandmother’, ‘brother-in-law’, or ‘sister’. The particular set of kinterms a child needs to know will obviously depend on the languages they’re learning to speak.

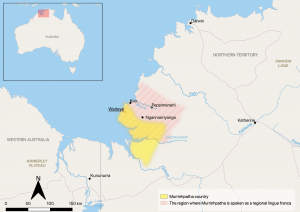

English-speaking children learn different words for mother and mother’s sister (‘aunt’), while speakers of many other languages learn a single term for these relatives.For example, in Murrinhpatha, a language spoken in Wadeye in Australia’s Northern Territory (see map), the word kale can refer to both mother and mother’s sister, among other relations. How do children figure out who can be grouped together under the label kale? From a broader perspective, how do children learn the kinship-related language used in their community?

English-speaking children learn different words for mother and mother’s sister (‘aunt’), while speakers of many other languages learn a single term for these relatives.For example, in Murrinhpatha, a language spoken in Wadeye in Australia’s Northern Territory (see map), the word kale can refer to both mother and mother’s sister, among other relations. How do children figure out who can be grouped together under the label kale? From a broader perspective, how do children learn the kinship-related language used in their community?

A new open-access paper just published in Language, ‘Acquiring the lexicon and grammar of universal kinship’, explores this question in Murrinhpatha. The paper was authored by Joe Blythe (Macquarie University), Jeremiah Tunmuck (Yek Yederr), Alice Mitchell (University of Cologne), and Péter Rácz (Central European University). Alice and Peter joined the project while they were post-docs working on the Varikin project, having met Joe at a kinship workshop held at the MPI for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany. Joe then visited the EXCD lab in January 2018 as a Benjamin Meaker Visiting Professor. After that their collaboration continued online across distant time zones.

One of the special things about Murrinhpatha kinterms is their ‘universal’ character, by which we mean that almost anyone in the community can be referred to with a kinterm. Working out how to refer to a newly introduced individual involves a kind of mental calculation based on telescoping chains of relatedness: if I know someone is my mother’s mother’s sister’s daughter, I can reduce that down to ‘mother’ and also refer to her as kale.[1] For Murrinhpatha people, information about kinship relations is so important that it’s expressed not just in vocabulary but also in the grammar of their language. In a sentence about two people doing something, part of the verb indicates whether those two people are siblings or not. For example, parraneriwakthadharra means, roughly, ‘They were following’, where it is grammatically specified that ‘they’ refers to two siblings.

Interested in how children learn this kind of kinship-related vocabulary and grammar, Joe designed two tasks: the ‘kinterms’ task, testing understanding of kinterms, and the ‘kintax’ task, testing understanding of the grammatical categories relating to kinship. In the kinterms task, Joe and Jeremiah showed children photos of their own relatives and asked them questions about kinship relations. There were three different types of questions: first, the researchers asked children straightforward questions, in Murrinhpatha, like ‘is this your cousin?’, where the children were expected to answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The researchers then went through a new series of photos and asked children what they called the person in each photo. In the third part, children were asked what the person shown in the photo would call them. Other research has shown that young children often struggle to identify who they are from someone else’s perspective, so we expected this part of the task to be the hardest. This vocabulary-oriented task was carried out with 24 children aged between five and sixteen.

Unsurprisingly, older children performed better on this task. We didn’t see any great age-related breakthroughs but rather a gradual improvement in children’s understanding of kinterms. We also found evidence that closer kin are easier for children to classify. This result is fairly intuitive, too, but what is notable here is that children’s learning partly follows culture-specific ideas about the relative ‘closeness’ of kin: children made fewer mistakes labelling a parent’s same-sex sibling than a parent’s opposite-sex sibling. While these two kinship categories can be considered similarly ‘close’ from a genealogical perspective, the language differentiates them, categorising a parent’s same-sex sibling as a parent, while providing a different term for a parent’s opposite-sex sibling. Nonetheless, biological parents were the easiest of all to identify, emphasising the importance of ‘closeness’ for learning kinship concepts, whether defined genealogically, culturally, or experientially. Our results also supported earlier research in other languages that taking someone else’s perspective on kinship relations is cognitively challenging.

The second task targeted participant’s understanding of ‘kintax’. Children saw a brief animation of people doing something, e.g., waving. At the same time they heard a sentence describing the activity, where the verb in the sentence indicated whether the people were siblings or not. Children were then shown two photos of people in the community, one showing siblings and the other non-siblings, and children were asked to choose the appropriate photo (see right for an example slide).

They were also shown slides and heard similar sentences that tested the understanding of number and gender, so these contrasts could be compared to their understanding of siblinghood. Joe and Jeremiah conducted this task with 39 Murrinhpatha speakers ranging in age from five to 40 years old. The most important finding here was that children’s understanding of kinship grammar progresses at similar rates to other grammatical categories like participant gender and number. Based on results from both the tasks, a complex picture emerges in which linguistic categories, general cognitive abilities, cultural practice, and individual experience all play a role in learning kinship vocabulary and grammar.

This new study moves our field forward on several fronts. It presents the first quantitative investigation of the acquisition of an ever-expanding kinship system; it’s the first study to investigate children’s acquisition of kinship-related grammar; and it’s also innovative in the way it tailored the experimental stimuli to each participant’s own family. This design feature meant that responses were not always directly comparable, which in turn restricted the statistical power of our analysis. Nonetheless, our results showed that children build up a gradual understanding of kinship that focuses on their closest relatives and expands to others as they get older. This supports a ‘focal’ theory of kinship terms, where at least some kinship categories are built from central exemplars and then extend to include more peripheral members. While our approach measured what children know, the next step is to explore how children learn kinship terms—a question that will involve more qualitative methods.

As part of my fieldwork with Datooga-speaking children in Tanzania, I’ve been conducting similar studies of children’s understandings of kin terms. Watch this space for updates on more papers addressing this topic.

[1] For the curious, this works via what anthropologists call ‘merging’ principles: a mother’s mother’s sister is classified as a mother’s mother, and a mother’s mother’s daughter is classified as a mother.